Technology goes viral

Around March 13 is when Suffield, Ct., First Selectman Melissa Mack estimates that she “saw the writing on the wall” with the coronavirus’s spread. The town’s chief executive witnessed the virus spreading in nearby New York City and Fairfield County, Ct., and she surmised it would soon get to her community in the state’s north-central sector.

So, Mack drove to every municipal building and met with every Suffield department head. She told each of them that she anticipated a transition to working from home, and she wanted them to brainstorm creative solutions for how government staff could take projects home and continue to offer public services while working remotely. She also asked them to think of other creative solutions for getting work done — perhaps to explore projects they hadn’t gotten to in years.

Town staff ultimately made many changes. Youth services held webinars on topics such as, “kids teaching kids about COVID-19” and found virtual ways to check-in with students and parents that could have more struggles due to the pandemic. Multiple departments loosened requirements where appropriate to allow email submission of various items. The town building official is allowing some inspections to be done over video calling.

Even Suffield’s parks and recreation department has begun offering virtual physical fitness classes, virtual field trips to places like national parks and museums, virtual arts and crafts programs and virtual classes — all of which are offered for free, Mack says.

“As a municipal employer, I’m thrilled that we’re able to show our community that our parks and rec department, while you associate them with active things and programs, etc., are still able to contribute to the town while working remotely. Because I certainly want to be able to continue to pay all of our employees to the extent I can continue to do so. And so, by showing that they are really actively engaged in working to support our community, [it] is wonderful,” Mack says.

Suffield departments aren’t alone in seizing hold of the digital space during this pandemic. Faced with citizens rightfully sheltering in place and practicing social distancing to flatten the curve, local government departments across the country have turned to technology to help serve citizens better at home.

Consider the Volusia County, Fla., Public Library, for instance. The library has 14 branches and lots of children’s programming — 600 children’s events have been planned for this summer, says Karen Poulsen, library project manager with the Volusia County Public Library.

Among those programs is live story time. Last fall, Volusia County Public Library staff had looked into doing pre-recorded bedtime stories and had compiled a list of books that people wanted read, Poulsen says. However, they needed publishers’ consent to read the books, and library staff didn’t get to contact the publishers for permission, Poulsen recalls.

So, fast-forward to the coronavirus pandemic. The Volusia County Public Library had to halt its programming and keep the public from coming in. But library staff still wanted to bring stories to their community in a personal way, since the community’s children know library staff.

“We just wanted to keep the literacy skills going for the kids and… that personal touch, have that familiar face,” Poulsen says. “And not being able to have them come into the branch, we still wanted to offer our programming, and this was, I think, a really good solution.”

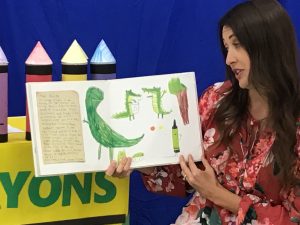

Poulsen found an online list of publishers that are allowing their books to be read online, but most of the publishers want their books read live. The library’s children’s staff decided to do live story reads three days a week over Facebook Live, while rotating between five locations. Library staff held their first reading on March 24, which received 972 views, she says.

Volusia County (Fla.) Public Library staff are virtualizing some of their programming to keep local children entertained while they observe social distancing and stay indoors.

The county has also offered puppet shows programming, as well as multiple arts and crafts videos on YouTube so that they can be viewed anytime, Poulsen says. That series includes a particularly timely video on how to make a DIY medical face mask.

“I’m just so proud of our staff. They really embraced this, and again, they’re so creative; I’m in awe,” Poulsen says. “I’m a children’s person at heart… so I just want to jump right in there and do all their songs with them.”

Chesterfield County, Va., also offered their residents a creative digital solution. But instead of increasing English literacy, their interactive Chesterfield Eats to Go map increases literacy of the county’s restaurants that are still offering pickup or delivery during the coronavirus outbreak.

Chesterfield County is a largely suburban community, so it doesn’t have the wide array of full-service restaurants that an urban area might have, according to Matt McLaren, senior project manager for the Chesterfield County Economic Development Authority. Part of the inspiration behind the map was to show residents the restaurants that they might not think of when trying to decide from where to get their next meal.

Because staff knew their list of restaurants wouldn’t be perfect per se, they included a form for omitted restaurants to complete to get listed on the map, says Woody Carr, Chesterfield County Economic Development Authority marketing, communications and research, and information technology division manager.

Chesterfield Eats to Go is published through the county’s existing GIS infrastructure, so it doesn’t consume additional resources, Chesterfield County GIS and Research Analyst Kathryn Abelt says. “This was really just taking advantage of our existing resources,” she says.

Creating the map also allowed for some additional outreach to the county’s business community.

“A lot of our work is very different all of a sudden than it was the day before, and we were trying to find different things we could do to reach out to different businesses that might not turn typically to the county economic development department or even the county government necessarily to get their message out there,” McLaren says.

As of April 3, the map had nearly 24,000 visitors since it launched around March 26, according to Carr (the county has about 350,000 residents). Carr adds that the map got more traction quicker than, “any other thing that we’ve done in the last few years.”

“It was almost like a, ‘what can I do while I’m sitting on my couch later at night after I’m done with my workday’ [thing] as well. That’s kind of how I looked at it as well,” McLaren says.

The Trenton, Mich., Police Department (TPD) recently began digitally harnessing geography to serve its constituents, too. For TPD, the idea came from a vendor with whom they had been carrying out a body camera pilot program for a few years, TPD Director of Police and Fire Services Steve Voss says.

Southfield, Mich.-based Equature had previously approached TDP a few years prior about using its Insight app, Voss says. The Insight app lets TPD send a text message to a 911 caller’s cell phone which asks the caller to open their phone’s camera. If they choose to open the camera, TPD is able to both see on a computer screen what the camera is pointed at, as well as pinpoint the caller’s location down to the room of a house in which the caller might be. The caller voluntarily grants permission to the app and can cancel the data stream at will.

“We have a lot of times when we receive 911 calls from cell phones, and it’s people who really don’t know where they’re at. They might not know the address, they might not know the cross streets,” Voss says.

Once the coronavirus reached the U.S., Voss began noticing that some cites were not sending first responders into environments that might have COVID-19 patients. Equature approached TPD again and suggested that the department could use the app in virus response, he says.

TPD had been sending one paramedic wearing personal protective equipment (PPE) into a COVID-19-related situation to assess it before potentially bringing other paramedics into the situation, according to Voss. The Insight app however, “allows us to pretty much put a paramedic on the other end of [a caller’s] phone and view the patient,” he says.

With the coronavirus pandemic going on, Voss posits that TPD could also use the app in non-serious calls to view evidence — like a car that was damaged or broken into — as well as identification over the phone, such that officers don’t have to arrive on the scene and potentially be exposed to residents who are coronavirus carriers and vice versa. This would be especially valuable in senior or assisted living facilities that house COVID-19-vulnerable individuals.

But TPD is still in the early stages of implementing the Insight app, just like Chesterfield County, Suffield and Volusia County are in implementing their new digital programs. As the coronavirus pandemic continues to play out, these local governments will continue to find ways they can build on these online programs.

“I think [use of the app] is going to develop over time, Voss says. “But this was the right time to try it, because it could help us in this crisis.”