Renewable power plays

President Donald Trump’s proposed budget for fiscal year 2020 would cut the U.S. Energy Department’s Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy budget by about 70 percent — from $2.3 billion to $700 million — according to a March 9 report from Bloomberg. That office has researched multiple areas of renewable energy innovation, including tidal energy generation and reducing wind power’s costs to compete with coal.

While Congress has yet to approve the funding measure, the move further evidences the Trump Administration’s aversion towards initiatives that would curb climate change.

In the absence of federal leadership on climate change and renewable energy however, local governments across the country have taken up the mantle of securing renewable energy for their communities.

“Hundreds of cities and towns across the country have decided to go all in on renewable energy at this critical moment for our climate, while the federal government really continues a dereliction of its duty to protect Americans from the climate crisis,” says Jodie Van Horn, director of the Sierra Club’s Ready for 100 campaign.

Many paths exist for generating renewable energy, from building solar panels, wind turbines or other sorts of infrastructure to obtaining such energy from power purchasing agreements. In doing so, some cities are innovating the ways in which local governments obtain renewable energy.

Regardless of the path that cities take for renewable energy, there are multiple questions that city leaders must keep top-of-mind in determining how to pursue renewable energy initiatives — especially because renewable energy generation contains more benefits than just being an environmentally-conscious move.

Booting up the system

In many markets across the U.S., solar and wind energy have become cost-competitive and sometimes even more cost-effective than power from an electrical grid, says Matt Hobson, co-founder and principal of Energy Edge Consulting, a provider of energy-related consulting services. Tax incentives have contributed to this, but solar and wind power generation costs have also decreased over the past 3 to 5 years.

A prevalent question for local governments interested in renewable energy lies in whether to build renewable energy-generating assets or to obtain such energy from power purchasing agreements. Land availability, geography and capital access are the major issues for local governments to consider when making the decision, Hobson says.

“It’s a significant capital outlay upfront to build the facility,” Hobson says. “But once you do, there’s no fuel cost on an ongoing basis in the form of natural gas or in the form of coal or in the form of refueling a nuclear facility.”

Once assets like solar panels, wind turbines or hydroelectric facilities are built, they tend to produce renewable energy for 10 to 30 years and feature agreements that will last as long as 10 to 20 years as well, Hobson says. In contrast, many entities in the power industry are used to purchasing electricity on 5-year-or-less contracts.

“So, a lot of organizations have a little bit of heartburn with getting comfortable with a longer-term power purchase agreement and locking into a rate, knowing that the price of electricity on the grid is going to fluctuate,” Hobson adds.

The approach for cities interested in pursuing renewables differs by the city. “I don’t think there’s a plain vanilla approach to this,” says Sergio Blanco, senior project manager for Partner Engineering and Science, which provides environmental and engineering consulting services.

However, there are some common questions that city leaders should ask themselves as they think about renewable energy. “Definitely, it’s a broader study that a municipality needs to do, starting [with] asking themselves or knowing, what are the needs of the municipality, and what [do] the constituents want,” Blanco says. “And the third question that they usually need to answer is, what resources do we have available to do it, meaning financially and in terms of the deployment of the assets that they have.“

In seeking out renewable energy for their communities, many cities across the country have joined initiatives like the Climate Mayors and the Sierra Club’s Ready for 100 campaign, which advocates adopting environmentally-friendly measures and striving for certain goals by a certain date. The Ready for 100 campaign, for example, implores participating governments to commit to obtaining 100 percent of their energy through renewable means by no later than 2050.

One participating city is Boise, Idaho, which signed onto the Sierra Club’s Ready for 100 pledge on April 3. However, Boise has a legacy of innovative renewable energy use that already spans decades, due to its tapping of a minimally-used resource in the U.S.: geothermal energy.

Boise, Idaho: Breaking ground without breaking the ground

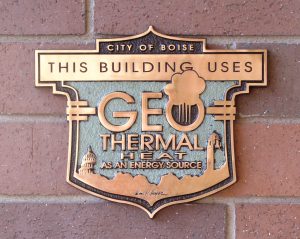

A plaque is placed on every building in downtown Boise, Idaho, that is hooked up to the city’s geothermal heating system. Art by Ward Hooper.

About 2,000 feet below the ground in Boise’s foothills lies a natural aquifer. Different areas within Boise have utilized the naturally hot water inside this aquifer in some way for heating purposes since 1892, according to Boise Director of Public Works Steve Burgos.

In the early 1980s, the city received a U.S. Department of Energy grant to install a geothermal heating system in downtown Boise. That system has gradually expanded over time to currently serve 95 buildings over about 6 million square feet in the city’s downtown area, according to Burgos.

“Over time, we just kept adding to the system,” he says. “Now, we’ve got it to the point where, any big buildings that come online, pretty much if they’re next to geothermal in Boise, it’s just what you do, you connect to the geothermal system. It’s very much a source of civic pride.”

Water from the aquifer is pumped to the surface through a fault line at about 177 degrees, according to Burgos. Two piping networks run across the city — a service line branches off from the mainline to run through buildings, where heat exchangers extract the heat from the water. That heat is used to heat the building, while the water drops to about 110 degrees. The water then travels to a collection system and is injected back into the aquifer, forming a closed loop.

Whenever a new building appears downtown, the city approaches its tenants and asks them if they’d like to opt into the system. Most building tenants choose to connect, and those that do connect receive a commemorative plaque noting their participation in the system, Burgos says. While many customers use it for general heating, the system has also been used to heat pools, heat laundry and melt snow on sidewalks.

Four smaller geothermal heating systems exist within Boise, and geothermal currently represents about 2 percent of Boise’s energy usage, Burgos says. Last year, the city received an increase in its water rights to pump more water for its geothermal system, and city leaders plan to expand the system to meet Boise’s Ready for 100 goals of being completely run on clean energy by 2035.

“We realize that it’s a pretty unique geographic advantage having that aquifer,” Burgos says. “So, like I said, having that 2 percent leg up of our community energy is a really big deal being geothermal. So, we certainly, we don’t ever take that for granted. It’s a pretty unique resource that we have.”

While geothermal energy is certainly a hallmark of Boise’s renewable energy portfolio, existing primarily below the ground means that it’s not necessarily the most visible structure.

One city in the Midwest, however, has experimented with introducing a highly visible landmark to reiterate its commitment to renewable energy, while also having it power one of its municipal buildings.

Milwaukee, Wis.: A testament to winds of change

In 2012, Milwaukee, Wis., made what was “probably the most significant renewable investment” it had yet done and built a wind turbine next to its Port Administration building to power it, according to Milwaukee Environmental Sustainability Director Erick Shambarger.

Milwaukee had received funds from the Energy Efficiency and Conservation Block Grant as part of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act and had made many internal energy efficiency improvements to its buildings, Shambarger says. However, city leaders wanted a “visible symbol of the clean energy economy” and had also set a goal of obtaining 25 percent of the city’s energy from renewable sources by 2025.

Thus, Milwaukee’s wind turbine was constructed on the coastline of Lake Michigan. “When people come in… on the ferry, that’s one of the first things they see in Milwaukee,” Shambarger says.

Milwaukee has made good on plans for using more renewable energy since the wind turbine went up — the city plans to buy more solar energy to power its libraries this year. In December, the city’s utility introduced new tariff programs that will also allow the city to procure more renewable energy moving forward.

The city’s wind turbine to date has produced 1,091,053 kWh of energy, which has saved the city approximately $120,000, or about $17,000 annually. However, a large urban area like Milwaukee is not an ideal place for a wind turbine, which requires a lot of land and of course, ample winds to function properly.

So, while a lakefront for a Great Lake provides enough wind resources for a turbine, Shambarger doesn’t expect that the city will do much more with the devices. Of Milwaukee’s lone wind turbine, he says, “it’s serving its purpose. I think it’s a nice, visible symbol of the city’s commitment.”

While power markets across the country can differ widely, wind and solar energy are cost-competitive and can even be more cost-effective than grid-obtained power in most markets, Hobson says.

Far south of Milwaukee, one rural municipal utility’s solar plant is trying to take full advantage of solar energy’s economics by legitimately chasing the sun.

Clarksville, Ark.: All the energy under the sun

Clarksville (Ark.) Light and Water’s solar power plant features 20,218 solar panels that generate enough energy to power about 25 percent of the utility’s homes.

Clarksville, Ark. is home to the largest municipally-owned solar plant in Arkansas. The plant is innovative for a few reasons —it was constructed quickly given its size, the plant’s financing works in the utility’s favor, its panels automatically rotate on an axis system and the plant could power a quarter of the city’s households, according to John Lester, general manager of Clarksville Light and Water (CLW).

While municipally owned, CLW operates autonomously from the city under a commission. As such, the utility drove the decision to pursue solar power generation more so than city officials.

“Obviously it’s the right thing to do,” Lester says of CLW pursuing renewable energy. “But it was the economics working — so, we were going to save long-term — that really tipped the scale.”

CLW was already committed to renewable energy before the solar plant was built. It has power supply contracts with organizations that generate energy from hydropower, wind and landfill gas sources. So, depending on weather conditions, parts of Clarksville’s power supply can consist of 50 percent renewable energy.

In 2016, CLW employees began noticing that solar was taking off in municipal utilities in Missouri, Lester says. Through distributed generation, CLW figured it could build a solar plant within the city, attach it to the city’s power distribution system and minimize transmission costs in being the only consumer of the solar plant’s energy.

“That’s the advantage to a lot of cities that may not even own their own utilities,” Lester says. “They can generate their electricity using solar at maybe a water treatment plant or a wastewater treatment plant. That would probably be a less expensive supply than buying it from the local investor-owned utility or electric co-op.”

CLW bought the solar power plant’s property and signed a lease agreement and a power purchase agreement with a private developer that built the plant, Lester recalls. The private developer will monetize tax credits for a six-year period and pass some of the savings to the utility. However, once the developer fully monetizes the tax credits, CLW has a pre-negotiated purchase price that it will pay for the plant.

The approximately 45-acre, 20,218 panel-plant was built in 90 days, fully delivering commercial energy starting on Dec. 23, 2017. “I couldn’t even get a permit in 90 days to sneeze in most towns,” Lester says.

The solar panels in Clarksville’s solar power plant are on an axis tracker system that faces east in the morning and gradually tracks the sun over the horizon until sundown automatically, Lester says. “The idea behind the axis tracker was, it would probably be producing energy at the time that my utility system peaked, and that would do what would be called peak shaving, which would reduce my demand, or my capacity charge,” he explains.

While the solar plant could power 25 percent of CLW’s households, the generated energy just flows into the grid, Lester says. Currently, CLW is contemplating adding more solar power at different locations around the city. A challenge the utility faces in the meantime is communicating the cost savings they’re encountering to utility customers.

“[Customers] don’t see this huge impact on their bill today. But it is moving in the right direction and it is going to continue to save money over the long-term,” Lester says of the plant.

Burlington, Vt.: A massive achievement

Wood chips like those featured here are fed into Burlington, Vt.’s McNeil Generating Station biomass plant to produce about 35 percent of the city’s energy.

In 2015, Burlington, Vt. — Vermont’s largest city — achieved a milestone in becoming the first U.S. city to be entirely run on renewable energy. Today, Burlington uses less energy than it did in 1989, according to Darren Springer, general manager of Burlington Electric Department (BED), the municipal electric utility serving Burlington.

BED obtains its energy from several renewable sources. Hydropower contributes 35.3 percent of BED’s electricity, 1.4 percent of it comes from solar and nearly 28 percent comes from wind sources, according to BED’s 2018 Performance Measures Report.

About 35 percent comes from another renewable source — the burning of wood chips through Burlington’s McNeil Generating Station biomass plant, which has operated commercially since 1984, according to David MacDonnell, BED’s director of generation. Wood chips are put into a large boiler, where the chips burn. Water in the boiler is then converted into steam, which hits the blades of a turbine. As the turbine blades spin, a connected generator transfers electricity onto power lines.

McNeil consumes about 76 tons of wood chips per hour, and the station can run on any combination of wood, gas or oil, according to BED’s website. About 95 percent of the wood used is logging residue and cull material that is created when higher value wood products are harvested.

While biomass energy is not nearly as commonly tapped into as wind or solar energy, it contains a number of benefits. “[Wood chips are] a solid fuel. You can have a real significant reliability benefit from having that type of facility. It’s a different power profile than wind or solar, which are more intermittent,” Springer says.

Currently, BED staff is looking into turning the McNeil plant into a combined electricity and heat generating station, according to Springer. An addition would be made to the plant to capture thermal energy, waste heat and steam and use them to provide partially renewable heat to Burlington residents.

However, the city has a larger goal on the horizon — by 2030, BED wants to make Burlington a net zero energy city, meaning that Burlington sources “at least as much renewable energy as it consumes in energy for electric, thermal, and ground transportation purposes,” according to BED’s website. BED’s goal is to make in-city travel net zero while lowering intercity travel’s impact.

“It’s definitely one of the most ambitious goals that a city or community has on climate in the country that I’m aware of,” Springer says.

In his state of the city address on April 1, Burlington Mayor Miro Weinberger announced the release of the Net Zero Energy City Roadmap this summer to analyze Burlington’s energy use and to outline strategies for achieving the goal, a city news release states.

Springer advocates a diverse portfolio of renewables, partnerships with local utilities and energy providers, related incentives and regulations as well as public education opportunities as key to achieving what Burlington has accomplished and what the Sierra Club advocates in its Ready for 100 campaign — a city completely powered by renewable energy.

“The transition to renewable energy is an opportunity for cities to build a more affordable and democratic, locally-controlled energy system as well as addressing the effects of climate change, and other local needs such as high energy prices and pollution,” Van Horn says.