Fueling opportunity

Seven years ago, Columbus, Ohio consumed 3.6 million gallons of petroleum fuel. By the end of last year, that number was down to about 3 million. “We still consumed about 3.5 million gallons of fuel last year,” Columbus, Ohio Fleet Administrator Kelly Reagan says. “A little over a half million of those gallons are gaseous fuels.”

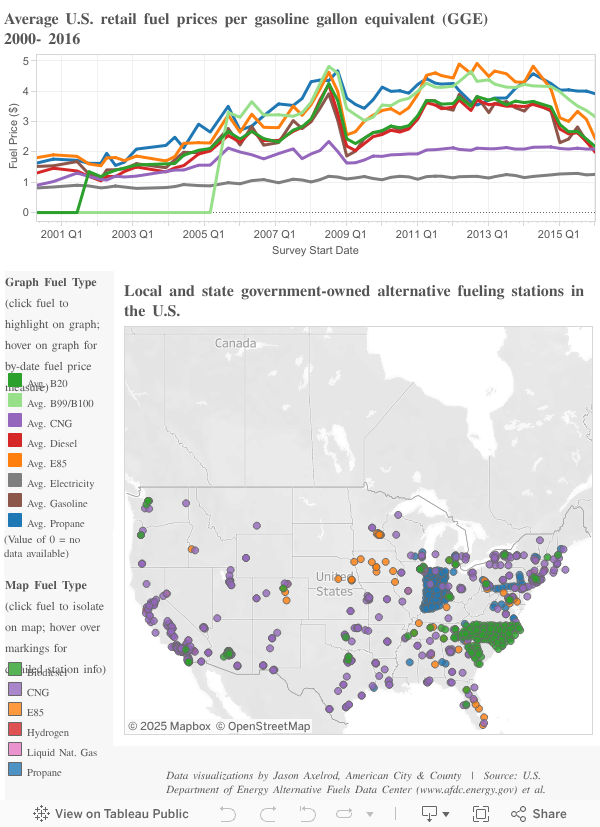

While many government fleets are employing alternative-fueled vehicles, the prevalence of such vehicles and the fuels they utilize vary widely across fleets.

Of the 445 vehicles in Boulder, Col.’s fleet, 105 of those vehicles are biodiesel capable, 173 are E85 capable and one is propane-fueled. In contrast, Norman, Okla.’s alternative fueled fleets consists only of flex fuel vehicles and compressed natural gas (CNG) vehicles. Norman Fleet Superintendent Mike White says that the city places a high emphasis on CNG vehicles.

“Our first preference is CNG, and when it is not available, we’re committed to buying top three in any fuel class,” he says.

White’s most effective CNG-enabled vehicles? His refuse trucks.

“They don’t have the complicated diesel emissions systems on them that have some setbacks, some complications for the drivers,” White explains.

White isn’t alone in that sentiment — CNG has proven particularly effective for refuse vehicles in general. Manufacturers such as Labrie Enviroquip Group, Ford Motor Company and Heil all offer CNG-enabled refuse vehicles.

Reagan and Salt Lake City Sustainability Director Vicki Bennett both say that CNG-enabled refuse vehicles make up sizable portions of their CNG vehicle fleets.

CNG’s operational advantages for refuse vehicles apply to their routes and the location of CNG fueling stations, according to Labrie National Sales Manager Skip Berg.

CNG fueling stations can be built in centralized locations like staging yards. Because refuse vehicles run on fixed routes, they always end up back at a staging yard, where a CNG filling station would be located.

Many CNG stations are called “time fill” stations, where a CNG truck gets hooked up to a compressor (the CNG fueling apparatus) and the tank is gradually filled overnight. This method ensures the gas is filled to capacity. “Now, no one is spending time at the end of their route lining up to fill their fuel tanks,” Berg explains.

Bennett, Reagan and White also expressed their preferences for buying new CNG-enabled vehicles — and alternative fuel-enabled vehicles in general — instead of converting petroleum-fueled vehicles.

“We did try some conversions a few years ago, and generally, we found that when we tried that, the systems didn’t go well together,” Bennett says. “We ended up with maintenance problems. It’s been so much better to buy them as new vehicles.”

White says that the Norman government has not converted older vehicles, due largely to the contrast in ROI on new vehicles versus converted vehicles.

“It is a pretty large upfront cost to [convert vehicles], and most of our older vehicles were seven, eight year-old pickups,” he says, “And by the time we put [in] a large investment of CNG, we wouldn’t have [them] in our fleet long enough to have a good return on investment.”

CNG has disadvantages when applied to refuse vehicles. According to Berg, four gallons of diesel fuel occupies the same volume as one diesel gallon equivalent of CNG. Engineers have solved this by installing tank mounts on different areas of the vehicles.

Although Reagan says the investment in a natural gas fueling station can cost between $500,000 to over $7 million, he and White have seen success in building CNG stations that also are available to the public,.

“We made a policy decision that if we’re going to be investing this kind of money in infrastructure, that not only should we be using the CNG, we should be making it available to fleets across the county as well as the general public,” Reagan says. He adds that the general response has been “overwhelmingly positive.”

Norman opened a CNG station for public and private use in 2012, which has worked well for the city and its residents. White says that between public and private use, the station regularly sells around 25,000 gallons of CNG monthly.

“We have totally exceeded our five-year expectations of where we thought we’d be,” he says. “We’re actually in the process of adding additional storage to it right now to try to keep up with the demand.”