Blowing up the benefits package

Faced with an adverse legal decision and skyrocketing benefits costs, Orange County, Calif., is pushing hard to reduce its pension and healthcare expenditures that have continued to rise, despite declining revenues, in recent years.

Employees now share in the contributions to their pension plans, pick up more of their healthcare expenses and hold slim prospects for an increase in wages or even small adjustments to keep up with inflation.

“If there was a truck full of money that backed up into the county, we would be the first to go to our employees and say, ‘Here it is, go for it,’” says Steve Danley, the county’s director of human resources. “But our financial situation is not such that we can do that.”

Instead, Danley says, he is bargaining with unions to find savings, so the county can manage its employee costs, particularly those for pensions and health care, and repay the state following a $150 million loss in a court case related to school funding. “Our pension and health care costs have increased dramatically,” he says.

Governments of all sizes are taking a strategic view of their human resource operations to assess how they can fulfill their mission in an era when cutbacks in pensions, wages, benefits and personnel have fundamentally changed the workplace.

New laws, court decisions and economics since the 2008 recession have combined to forge a new reality that is vastly different from the world of ample pension plans and rich healthcare benefits that were once the trademark of public sector employment. Now, governments seek innovations that will motivate their employees, control costs and keep them competitive in the hunt for the right people in an increasingly technical world.

“If employers aren’t doing a strategic assessment, they should be thinking about doing it,” says Julie Stich, director of research of the International Federation of Employee Benefit Plans, based in Brookfield, Wis. “There have been so many changes.”

Cities and counties around the nation have assessed their workforces and initiated changes to embrace the new environment. For example:

Cities and counties around the nation have assessed their workforces and initiated changes to embrace the new environment. For example:

Coconino County, Ariz., allows its 1,200 employees to job share, phase into retirement and purchase up to 10 personal days a year;

The California Public Employees Retirement  System, known as Calpers, has adopted a healthcare payment policy for some public employees that fixes a pre-set cost for a given medical procedure that a group of hospitals has agreed to accept;

System, known as Calpers, has adopted a healthcare payment policy for some public employees that fixes a pre-set cost for a given medical procedure that a group of hospitals has agreed to accept;

Elgin, Ill., laid off 80 employees, and its unions made concessions in their compensation and benefits, but the city doubled the budget for employee education and training and for improved technology;

The City and County of San Francisco offer telecommuting and leave policies and allow retirees to be hired for short-term projects;

Atlanta, Ga., which in 2010 had only half the necessary assets to meet its pension obligations and was spending 20 percent of its budget on pensions, put in place a new retirement plan that requires employees to contribute an additional 5 percent of their wages to the city pension system. The plan also reduces the cost of living adjustment for future employees to 1 percent. Most future city employees will receive a much smaller pension and be placed in a 401(k) style plan;

Carlsbad, Calif., did away with automatic step increases for years of service and placed the savings in a pool for merit increases.

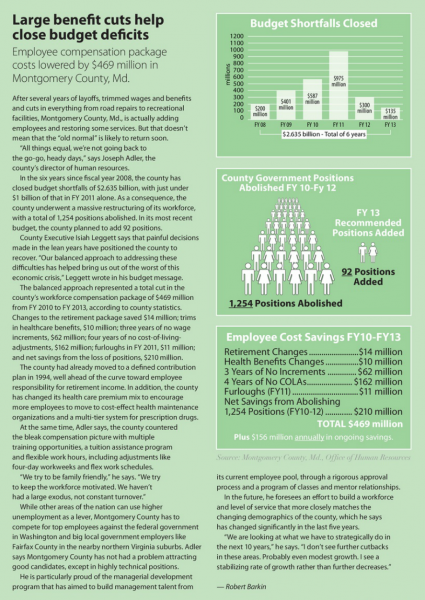

To see how large cuts to benifits helped reduce budget deficits in Montgomery County, Md., click the image on the right to expand.

Pension and health care cutbacks

While the political argument remains heated in the background, local government officials are working every day to contain costs within budgets that are stretched thin, with little public appetite for tax increases or a reduction in essential services.

“The level of change in the public sector is unprecedented,” says Elizabeth Kellar, the chief executive of the Center for State and Local Government Excellence (SLGE), a Washington-based research organization. “It is one of the most significant challenges for government leaders going forward.”

Cathie Eitelberg, the national public sector market director for The Segal Group, a national benefits and human resources consulting company, says governments have to make a comprehensive assessment of their HR operation. “Every entity is different,” she says. “It’s a strategic process. And there’s no one right answer. Each just has to go through it and figure out what it needs to focus on to deliver services to their constituency.”

Local governments have lopped off 3.5 percent of the public sector workforce from peak employment in 2008. Governments employ about 6.3 million workers today, excluding education, according to SLGE and government statistics. In addition, SLGE found that the workforce has aged, from an average age of 40 in 1992 to 45 in 2012, as more workers decided against retiring during hard economic times. In its annual Workforce Trends survey, SLGE found that 60 percent of governments say their workforce is smaller today than in 2008.

At the same time, local and state governments made significant changes to benefit programs in the years since the onset of the Great Recession, which exposed huge gaps between the promises that had been made to employees and the employers’ ability to fulfill them.

The most obvious difficulties arose in the public sector pension system, which held $2.8 trillion in assets in 2012, covering 15 million working members (about 11 percent of the nation’s workforce) and provided regular benefits to 8 million annuitants, according to Alicia Munnell, director of the Center for Retirement Research (CRR) at Boston College.

According to the National Association of State Retirement Administrators, 48 states enacted major changes in state retirement plans for many groups of employees from 2007-2014, including: suspending or lowering cost-of-living adjustments, increasing employee contributions, reducing benefits for new hires and changing defined benefit plans (where the employer has the risk for delivering the benefit) to hybrid plans that contain some element of a defined contribution plan (where the employee is responsible for the final benefit.)

These changes have improved the prospects for state and local pension plans, according to Munnell’s statistics. It notes that the aggregated state and local plans should be back to a solid 80 percent funding by 2015, notwithstanding a crisis, such as a stock market crash.That aggregate ratio had fallen as low as 75 percent in 2011, according to CRR.

While the overall picture has improved, the finances still vary widely from plan to plan, with 14 localities declaring bankruptcy in the past five years, often to shed their pension obligations, and plans in other entities with funding levels near 50 percent.

Widespread cutbacks have also been seen in the area of health care, with 52 percent of employers in the SLGE study responding that they have shifted more health care costs from the employer to employee, in areas such as higher premiums, co-payments and deductibles. While health care inflation has slowed in the past two years compared to the regular increases of 8 to 10 percent several years ago, no one knows if those kinds of devastating hikes will return. In addition, certain provisions of the Affordable Care Act will penalize employers whose plans do not do enough to control costs.

To read about the differences of opinion between unions and taxpayers, click the image on the right to expand.

Benefit reductions decrease job appeal

As a result, employers are trimming benefits, and those reductions are having a negative impact on the workforce in communities around the country, according to the SLGE survey. About 70 percent of the employers cited employee morale as an important issue for their organization. And the number of positions that employers say they have a hard time filling has grown, ranging from dispatchers and seasonal pool employees to attorneys, engineers and first responders, while the pace of retirements has accelerated in the last two years, after slowing down in the first years of the recession.

“It’s surprising how difficult it is to hire certain skill sets,” says Kellar. “We see the list growing every year.”

Although Linn County, Iowa, does a good job of marketing itself as a desirable place to work, the county, like all governments, has to fight a generally negative perception about public service, says Supervisor Linda Langston, a Board of Supervisors member.

“When I go to nearby universities to talk to potential graduates in public administration, I always ask who is going to work in the public sector,” she says. “No one raises their hand.”

Langston, who also is currently serving as the president of the Washington-based National Association of Counties (NACo), says that employees still like working for Linn County, despite seeing health care premiums triple, with large increases in deductibles in the last 11 years. “It’s increasingly become a sticking point in negotiations,” she says. “It’s more and more of a problem.”

And she hears the problem also in her work with NACo. “On the national level, people are talking about it all of the time,” she says. “People want more information so they can sort this out.”

She also sees big changes coming in the area of pensions, which she calls “a tsunami wave,” as more governments move from defined benefit to defined contribution plans. An area of concern, she says, is assisting employees who now must assume more responsibility for their retirement. “This is a broad, complex area,” she says. “I’m not sure officials understand the challenges they will confront in the next eight to 10 years.”

Since governments can only offer small wage increases in the near future while more healthcare cost shifting is likely, officials try to be creative in improving the overall workplace, she says. “We do surveys, trying to see what are the best plans we can offer,” she says.

And Langston believes that the unions serve a valid purpose on behalf of the employees, though they put up tough fights during negotiations on sensitive issues. “We try to tell the unions that world has changed,” she says, “but they are living in a world that existed 30 or 40 years ago. Cogs are moving at different rates of speed.”

Adding contractors rather than employees

Adding contractors rather than employees

In Rancho Cordova, Calif., outside Sacramento, the city of 67,000 residents has more contractors for its services (90) than it has full-time employees (68), says Stacy Peterson, the HR manager. “It gives us flexibility to reduce contracted services when development is down,” she says.

The city has private companies maintaining roads as well as providing city planners and inspectors, she says. Many of the contract employees have served the city for five or even 10 years, but their employers handle all of their pay and benefits.

Although much of the workforce is not employed by the city, it makes an effort to include contract workers in city planning task forces and community volunteer efforts. “We take extra steps to incorporate them with the workforce,” she says.

The city takes pride in its designations on various “best of” lists, she says. “We have a very highly engaged workforce. Employees want to come to work. We’re able to recruit top talent.”

Adding wellness programs to save money

At the Capital Metropolitan Transit Authority in Austin, Texas, the human resources department estimates that it has saved $4.5 million through its wellness programs. The programs were designed to control healthcare costs that were soaring 10 to 15 percent per year, says Michael Nyren, the agency’s risk manager. “It was threatening the overall operation of the agency,” he says.

The sedentary nature of driving buses, high incidences of smoking, an average age approaching 50 and rampant diabetes all combined to create “a slew of challenges to change the attitude and approach to health,” he says. “We wanted them thinking about health and nutrition.”

Taking a comprehensive approach, the agency launched many initiatives, including promoting its fitness center, changing the food in the vending machines and giving cash incentives to quit smoking. “You have to spend money to save money,” he says. “But the costs were small compared to what we saved.”

A new challenge is the imminent conversion of the workforce from agency employees to contract status, as part of a cost-saving effort that could reduce costs by $35.5 million over seven years. “We’re trying to find a way to track healthcare costs,” he says, noting that some of the cost information will be proprietary among the competing contractors. “The goal is to find a way to measure the impact; it’s critical to what we do.”

In Orange County, Danley says that the cuts have not diminished the supply of candidates for openings in the county, partly because the long driving distances in Southern California make the local job market especially attractive. “We’re still getting tons of applications,” he says.

Comparatively, he notes, the pension benefits in the county are still better than in the private sector. “Even with the reduced pension, people come knocking on the door,” he says. “Maybe you can’t retire at 55, and have to wait until you’re 62, but after 30 years, you get a full pension walking out the door.”

_____________

To get connected and stay up-to-date with similar content from American City & County:

Like us on Facebook

Follow us on Twitter

Watch us on Youtube