A state’s role in averting municipal financial crises

States have adopted several methods to deal with municipalities in financial distress – some with greater successes than others, according to “The State Role in Local Government Financial Distress,” a report recently released by the Pew Charitable Trusts.

During a webinar associated with the report’s release, Kil Huh, Pew’s director of state and local fiscal health, said the reasons for municipal financial distress are multifaceted. With no best practices for intervention established, Huh says states should use 3 basic principles to avoid or, if necessary, intervene in local financial issues:

Proactivity – monitoring local government finances can help avoid financial crises and send a positive message to bond markets.

Understanding tradeoffs – Policymakers must understand if they are able to intervene and at what level they will be able to do so, given constrained state budgets.

Transparency and communication – Intervention programs should involve all stakeholders in discussions, should be transparent with all financial information and should return control to local officials as quickly as possible.

In addition, the study found:

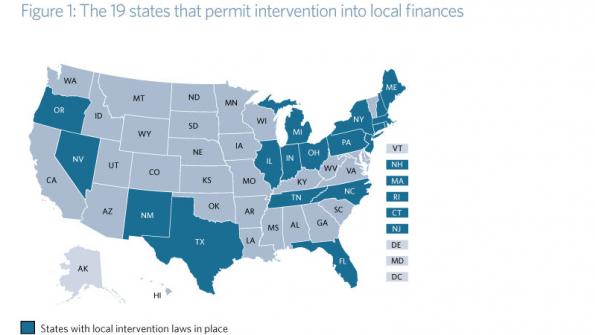

- Only 19 states have laws that allow intervention in local governments’ finances.

- In most cases, the interventions are reactionary, rather than proactive.

- States usually intervene to protect their own interests and those of other municipalities, to enhance economic growth and to maintain public health and safety.

- Often, local officials resent state involvement in local financial affairs.

Huh says the reasons for a municipal bankruptcy can usually be traced back to four factors: a bad investment decision, a failed infrastructure project, a costly legal decision or the rising costs of pensions.

Historically, Pew found some states have been more aggressive than others in dealing with local financial problems. The report notes that Michigan, North Carolina, Pennsylvania and Rhode Island are among the states with the most aggressive assistance programs. New Jersey decides its involvement based on the case’s severity, while California and Alabama take a “hands off” approach.

The report noted a lack of intervention in Jefferson County, Ala., and several California cities, including San Bernardino and Stockton. It says the hands off approach has been used in part because of the unwillingness by state officials to become involved in local matters. However, the report found that a hands off approach often extends the time for a resolution to the issue, citing Jefferson County’s four-year struggle.

The report states that for several years, New Jersey’s state government has been working with Camden, one of the state’s poorest cities, eventually assuming control of the city government, school system and police department. Historically, cities have worked well with the state to avoid insolvency, with transitional aid being the goal; however, Camden has proven difficult to pull out of financial ruin, demonstrating that that there is no “one size fits all” solution.

Rhode Island pulled Central Falls out of bankruptcy in less than a year by ensuring bondholders be paid in full, and North Carolina’s nearly 80-year-old monitoring program has kept its municipalities in the black despite a sluggish economy, according to the report. Pennsylvania and Michigan are both deeply involved in local governments finances, but, as Detroit’s recent bankruptcy demonstrated, monitoring sometimes is not enough.

Regardless of approach, Huh says, “a lot of pain is involved” when cities declare financial emergencies. Solutions can include increased taxes, decreased populations and damaged reputations. And while there is no universal solution, he says proactive, preventative measures can help stave off financial collapse.