Electric utilities begin delivering all-day power

The March 1914 edition of The American City included a description of an initiative in Kansas City, Kan., to expand the use of electricity generated by the city’s new light plant, which began operating in November 1912. The commissioner of the light plant, L.H. Chapman, noticed that most of the plant’s energy was used for lights at night, but the equipment generated electricity all day, and he thought there should be some way for residents to use the electricity during the day. According to the article, his wife asked, “Why can’t you let the women cook with it?” At the city’s regular rate of 6 cents per kilowatt hour, cooking with electricity would not be competitive with the cost of cooking with natural gas. So, he consulted several electrical engineers, and they agreed to a test in which they would sell current for 3 cents per kilowatt hour for cooking.

The March 1914 edition of The American City included a description of an initiative in Kansas City, Kan., to expand the use of electricity generated by the city’s new light plant, which began operating in November 1912. The commissioner of the light plant, L.H. Chapman, noticed that most of the plant’s energy was used for lights at night, but the equipment generated electricity all day, and he thought there should be some way for residents to use the electricity during the day. According to the article, his wife asked, “Why can’t you let the women cook with it?” At the city’s regular rate of 6 cents per kilowatt hour, cooking with electricity would not be competitive with the cost of cooking with natural gas. So, he consulted several electrical engineers, and they agreed to a test in which they would sell current for 3 cents per kilowatt hour for cooking.

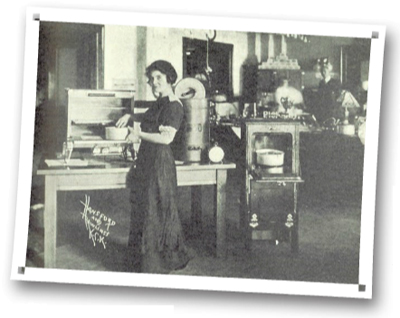

The city placed electric cooking appliances in 10 homes and recorded the exact cost of cooking each article of food. When that test proved successful, the city organized a four-day show at City Hall featuring electrical appliance demonstrations that attracted approximately 10,000 attendees. Based on an informal survey, the light commissioner determined the last obstacle to overcome would be the price of the appliances. So, the city set up a municipal store in the City Hall basement out of which it sold discounted electrical housekeeping appliances, including stoves, irons and washing machines. The special 3-cent rate for cooking was recorded by a meter installed in each home that used a cooker, and an engineer from the municipal plant would visit the homes to give instructions in how to cook with the least amount of current.

The idea that cities should encourage residents to use more electricity was repeated in an unsigned July 1935 article, “Now is the Time for Municipal Electric Utilities to Build Load.” The article stated that cities with power plants had the potential to make a lot of money by reducing their rates during the day and convincing residents to buy electrical appliances, which have “the extra advantage accruing from letting electricity do as much as possible of woman’s drudgery.” “The thing to sell is not an electric range but a happier woman, and in some cases the husband is the better prospective buyer,” the article suggested.